新藥研發,由實驗室發掘新成分、評估作用機轉、量化生產、劑型設計、動物毒理試驗、臨床試驗到上市應用於治療,平均費時十年以上,本文介紹研發的過程。

文 / 鄧哲明(台大醫學院藥理學科特聘教授)

醫藥衛生科技可以反應一個國家之現代化水準,過去由於醫藥之環境、政策、與人才等因素,我國生技醫藥產品之自製與研發能力不足。然而二十多年來台灣經濟非常快速成長,也成功的漸漸由勞力密集之加工中小企業轉向高收益之科技製造業。隨著半導體、電子、資訊之成功發展為世界級之高科技產業,政府為了確保未來經濟之永續發展,也將生技醫藥訂定為我國八大重點發展科技之一。行政院自1998 年起也在多次「生物技術產業策略會議」中都再度強調、規劃,並於2009 年提出「生技起飛鑽石行動方案」之發展策略,責成政府相關部會與國內研發機構盡速執行。因此,新藥研發將是我國生物科技產業未來之重點方向。

一個新藥的誕生,由實驗室到產品上市,研發時程長達10~15 年,所耗資金達150~200 億台幣。由於藥物的研發相當複雜,因此本期「新藥開發」專輯的一系列文章中先介紹新藥的研發流程,給讀者一個整體的概念。

藥物發展歷史

人類對於生、老、病、死,不只想了解,也想尋找解決問題的方法。有文字記載之文明古國,都可以發現這些早期之醫藥記載(中國,西元前2800 年;巴比倫,西元前2600 年);古代藥物多取自動植礦物(尤其天然草本),如記載在神農本草經集(上中下品共365 種)、黃帝內經、難經內之藥物;埃及在西元前1500 年也記載藥物700 種,處方800 種。直到1493~1541 年瑞士之科學家帕拉塞爾蘇斯(Paracelsus)才以化學應用於醫學,用汞治療梅毒,並提出藥與毒是因使用劑量不同而異之藥理概念,因此後人稱他為藥理學之祖。

1803年德國藥師賽特納(Sertürner)由鴉片中分離出白色結晶成分——嗎啡(morphine),開啟天然物純化之先例。1846 年美國青年科學家莫頓(William Morton,當時為醫科二年級學生)第一次使用乙醚於外科麻醉(在美國Boston 公開臨床實驗),使病人能在無痛、無知覺下進行開刀。1897 年德國Bayer 公司之藥理學家霍夫曼(Felix Hoffman)為改善患有風濕性關節炎的父親,因服用水楊酸(salicylic acid,抽取自柳樹)之鈉鹽對胃有刺激性之副作用,加入醋酸製成刺激性較低之乙醯水楊酸(acetylsalicylic acid),成為孝子製藥之佳話,Bayer 公司並取名阿司匹林(Aspirin),於1897 年發售至今115 年歷史,百年來它還應用在消炎、止痛、解熱、抗癌等用途。

阿司匹林之研發歷史

| 400 B.C. | 希臘名醫 Hyppocrates 採用白楊樹的汁液為痛人止痛、退燒。 |

| 1828 | 德國Buchner由楊柳樹皮抽出成分水楊苷(salicin)。 |

| 1838 | 義大利 Raffae Piria 證明 salicin 是一配醣体,並將其分離,水解成 salicylic acid。 |

| 1897 | Bayer 公司之 F. Hoffman 將salicylic acid 加入醋酸(acetic acid)合成並純化出 acetylsalicylic acid(取名Aspirin)。 |

| 1904 | Aspirin由粉末改為錠劑,服用劑量準確、方便。百年來,使用於風濕痛、止痛、消炎、解熱、抗血栓、抗癌等用途。 |

| 1971 | 英國John R. Vane 於《Nature》期刊發表Aspirin作用機轉為抑制前列腺素合成,1982榮獲諾貝爾生理暨醫學獎。 |

|

|

歷史上,人類生命最大的威脅之一是傳染病,病原菌的感染一直沒有很好的藥物,因此造成傳染、流行與死亡。磺胺藥物於1936 年問世,具有制菌作用,而第一個抗生素——青黴素(penicillin)於1941 年上市,具有殺菌作用。這些藥物較選擇性對抗細菌,但對被感染之宿主(如人與家畜)則副作用較小,因此降低細菌感染引起之疾病,也延長了人類之壽命。而現在已開發國家之十大死因,則多非感染性,而是癌症、心血管及代謝疾病(如高血脂、高血糖),這些疾病的治療也是世界各大藥廠急著解決,研發新藥的方向。

藥物研究與發展

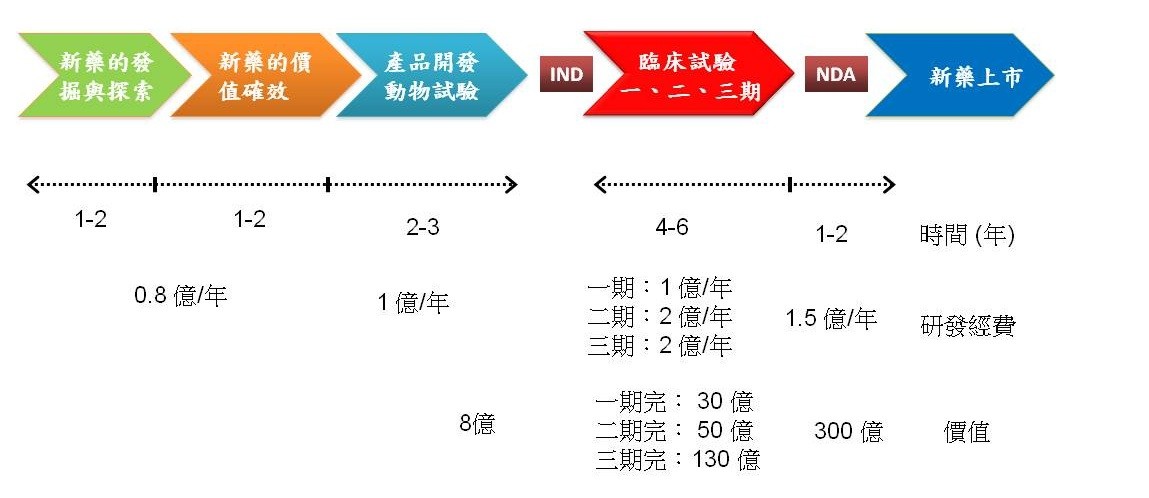

藥物的研究(research, R) 與發展(development, D),雖然都是在研究藥物,但其意義與目的是不同的;前者是較偏向藥物的探索、作用與機轉之研究,是學術創新性;而後者是對具有治療應用價值之藥物進行產業化或商品化之開發,包括藥物的製造、動物的毒性到臨床藥效之觀察等。整體新藥研發(New drug R & D)的流程包括:藥的探索與價值確效、產品開發之臨床前動物試驗、臨床試驗,具有臨床療效後,才能查驗登記並上市。整體研發費時10~15 年,每一段都要花費相當龐大之研發經費,然而新藥研發一旦成功上市,其產值卻也非常龐大(圖二)。

以下詳述重要之研發三大階段:

一、藥物探索(Drug discovery)

此階段包括新藥的發掘及其價值確效。現代醫療用藥物的重要來源包括:小分子化合物、蛋白質藥物、植物藥(含中草藥)。目前臨床上使用的藥物仍以化學合成之小分子化合物為主;蛋白質藥物包括抗體、荷爾蒙、疫苗等;而植物藥或中草藥包括傳統複方、單方、萃取植物性新藥。

小分子化合物:一個藥物由發現作用到成為真正有用的新藥,是一件費時費錢的投資,通常一萬個才有一個真正成功上市。一個有藥效之化合物(先導藥物,lead compound),通常需再合成千百個衍生物,評估並比較其活性、毒性、安定性、藥物動力學後,選上數個具有潛力者(候選藥物,candidate )進入下一階段之臨床前試驗。為了加快藥物研發的時程,藥廠或研究機構會有不同的策略,如以組合化學(combinatorial chemistry)來加快合成藥物的數量,並配合高效率篩選機器(high throughput screening)來評選出有效之化合物。有時需借助電腦,了解藥物與生物體結構之相互反應,來設計更具選擇性之衍生物,以提高藥效,降低副作用,並減少實際合成化合物之數量與成本。

蛋白質藥物:蛋白質是人體重要組成,也有許多生理功能,如荷爾蒙、酵素、各種細胞激素(cytokines)等,因缺少而引起的疾病,可補充該蛋白而得到舒解;例如血友病可補充凝血第八、第九因子。蛋白質藥物具有高度選擇性,但外來之蛋白會因與體內原有分子間的小差異而呈現抗原性,造成副作用。早期蛋白質藥物多靠純化得到,例如治療血栓之血栓溶素(urokinase)是由收集人的尿液經乾燥、分離、純化得到;止血用之纖維蛋白原(fibrinogen) 則由血液純化得來。由於生物科技的進步,目前大部分蛋白質藥物常靠基因生物工程(gene biotechnology),藉由細菌或哺乳類動物細胞的來源製造。

植物藥:中藥大多以複方為主,即處方中會有多種草藥,並強調君、臣、佐、使之中國傳統醫學概念;而歐洲的植物藥則以單一草藥為主。美國為了鼓勵植物藥成為臨床用藥,因此制定植物性新藥規範(Botanic Drug Guidance, 2004), 強調藥效與安全,而藥物的純化與成分鑑定為非要件,可惜近十年來獲美國FDA 通過的成功案例不多。我國也鼓勵由中草藥進行部分純化,以達到去蕪存菁之植物性新藥研發,目前有不少件植物性新藥正在臨床試驗階段,希望是一條走上科學化中草藥的新策略。

藥效篩選與作用機轉探討:藥物的生物活性評估是一件非常複雜的工程,因不同目的而採用離體(in vitro) 到活體(in vivo) 試驗: 酵素、受體(receptor)、G–蛋白、細胞、組織、器官、活體動物到各種疾病動物模式。藥物作用機轉的探討是藥理學家之專長,能了解作用之分子層次,不只有益於合成、改良最適化(optimization)之藥物,且能瞭解藥物之所以有藥理療效、生理反應、副作用及藥物間交互作用之依據。

專利申請:新藥研發既然花費相當大,為了保障這些研發的智慧與技術,都會申請專利。藥物的專利申請,包括新物質(new product)、新製程(new process)及新適應症(new indication)等,藥廠都有不同的策略與申請時程,以便對新藥的智財權作最大的保護,減少他廠仿冒之機會。

二、臨床前試驗(Pre-clinical toxicological tests)

此階段包括產品原料藥之開發、製程、劑型及動物毒理試驗等。藥物最終目的是要在病人身上證明有效,但為了安全起見,一定要先在動物證明其具有藥效,並且安全。為達此目的,有許多試驗是在人體臨床試驗前必須完成,才能向衛生主管機構申請「試驗用新藥」(investigational new drug, IND),通過審核後再執行臨床試驗。以下簡述IND 所需完成之研發項目。

( 一) 化學、製造與監控(Chemical Manufacture and Control, CMC):含化合物的大量製造、純度分析、物化性質、安定性試驗、劑型設計等。

(二)藥物動力學(Pharmacokinetics, PK):了解藥物如何在體內被吸收、分佈、代謝、排泄,這些資料可提供未來臨床試驗將以何種給藥途徑使用(如口服、針劑、吸入劑等)。

( 三) 安全性藥理(Safety Pharmacology):為評估對療效以外之作用,需進行動物安全性藥理試驗,以了解可能之副作用,尤其對心血管、呼吸、中樞神經等之影響。

(四)毒理實驗(Toxicology):毒性試驗種類相當多,包括:急性毒性、亞急毒性、慢性毒性、生殖毒性、致癌性、致突變性等。為了加速新藥能及早驗證是否有療效,有些耗時費錢之毒理實驗(如致癌性、生殖毒性)是可容許在臨床試驗一、二期時再執行。

上述這些臨床前試驗的工作,不一定要藥廠本身執行,可以委由具有此專業設備與經驗之委託研究機構或公司,即所謂CRO(Contract Research Organization)代為執行。市場上有種種不同功能與技術之CRO公司,一個藥廠可借助多家CRO 來完成一件新藥之研發,以節省設置那麼多研究機構之經費。而當臨床前試驗執行完畢後,即可收集所有研發相關之實驗結果、文獻等資料向藥物管理機構申請IND,其資料通常包括:藥物來源組成、製造方法與規格、藥理與毒理之各種動物實驗、藥物動力學、臨床試驗計畫書與執行者等。

三、臨床試驗(Clinical trials)

臨床試驗的執行都應在衛生主管機關核可之醫學中心或醫院執行,而且必須經過人體試驗倫理委員會(Institutional Review Board, IRB)之同意,以保障人體試驗的品質符合優良臨床試驗規範(Good Clinical Practice, GCP)。新藥的臨床試驗通常分成一至四期,其中一至三期是上市前申請「新藥查驗登記」(New drug application, NDA)所需。為了試驗的可信度,利用統計科學來嚴謹評估其臨床療效與安全性。參與臨床試驗的病人分為對照組與試驗組;試驗組給予研究之新藥,而對照組為已上市之藥物作比較,視情況亦可服用無藥效之佐劑當對照(安慰劑)組 。玆將一至四期之情形分別簡述如下:

臨床一期(Phase I)——以健康之志願者為測試對象,通常20~50 人,主要是觀察藥物對人體之安全性與藥理作用。隨著劑量的增加,觀察受試者之耐受程度與症狀,並評估藥物之吸收、分佈、代謝與排泄之藥物動力學,以了解藥品之安全性與治療之劑量。在抗癌新藥之人體試驗,由於使用之新藥毒性較大,會直接以癌症病人為對象。

臨床二期(Phase II)——以小規模之病人,通常50~300 人,評估不同劑量對病人之有效性與安全性,以作為第三期臨床試驗劑量之依據。對照組以上市之藥物作比較,並評估二者之藥效與安全性差異。

臨床三期(Phase III)——擴大第二期之臨床試驗規模,以250~1000 病人為試驗對象,依隨機分配法,將病人分類成試驗組和對照組;並依雙盲(double blind)試驗之準則進行試驗,即醫生與病人均不知那一組之病人吃的藥是真正的新藥,或是老藥或安慰劑。最後經嚴格的統計分折來判斷藥效與安全性,決定新藥是否優於(superior)或不亞於(not inferior)老藥,若新藥合乎上市許可之法規,即可向藥品管理機構申請新藥查驗登記(NDA)。

臨床四期(Phase IV)——亦名上市後臨床試驗監視期,主要目的是新藥上市後,大規模的病人群使用下,監視通報發現發生率極低之不良反應或嚴重副作用(severe adverse event, SAE)甚或死亡之情形;有些嚴重明確之副作用,將導致政府當局下令停止生產,並下架回收,例如抗關節炎藥物Vioxx 因嚴重的心血管疾病風險被迫於2004 年撤離市場。

藥物的查驗登記與與管理

每個國家對於藥物的管理都有一套制度,從新藥的IND、每一期的臨床試驗、到藥品的查驗登記(NDA)與上市後的監視,都是為了保障人類的健康。美國及台灣的醫藥品主管機構都叫食品藥物管理局(Food and Drug Administration, 分別為FDA 及TFDA),歐盟則成立了歐洲藥物評審調查局(The European Medicine Agency, EMEA)。藥物的審核,是相當嚴謹,食品藥物管理局有各領域專家群,針對藥物之CMC、藥理、藥動、毒理、臨床試驗給予詳細的評審。IND 的審查,是著重在安全比藥效重要,在一至數個月內可完成審查,通過後即可進入臨床一期試驗。NDA 的審查,由於資料龐大,且需在藥效與安全之多方面考慮才准上市,因此審核相當費時。美國FDA 考量許多無藥可治或迫切需求之重症病人,因等待新藥過久而失去機會,因此制定了快速核准制度(Accelerated approval),如愛滋病用藥與罕見疾病用藥等;但必須在執行上市後,建立各項藥物安全之限制設施。

孤兒藥或罕見疾病用藥(Orphan drugs):

依據美國「孤兒藥品法」之界定,罹病人數少於二十萬人之疾病,即屬於罕見疾病(orphan disease)。而我國「罕見疾病及藥物審議委員會」的公告,則是以疾病盛行率萬分之一以下作為我國罕見疾病認定的標準。由於新藥的研發非常昂貴,以利潤取向之藥廠自然對市場不大之先天性疾病不感興趣,政府為照顧這些病人,因此以相當的誘因來鼓勵藥廠研發孤兒藥,這包括減免稅金,並且核准後十年不核淮第二個同類藥物上市(專屬特賣),以相對保障產業權益。

銜接性試驗(Bridging study):

國際醫藥法規協合會(ICH)制訂了評估族群因素對藥品作用的影響之相關內容。我國衛生署規定,若申請新藥查驗登記時,該藥物未在我國執行過臨床試驗者,除依現行規定檢附資料外,應另檢附銜接性試驗計畫書或報告資料送衛生署審查。所謂銜接性試驗乃為提供與國人相關之藥動∕藥效學或療效、安全、用法用量等臨床試驗數據,使國外臨床試驗數據能外推至本國相關族群之試驗。

我國藥物研究機構

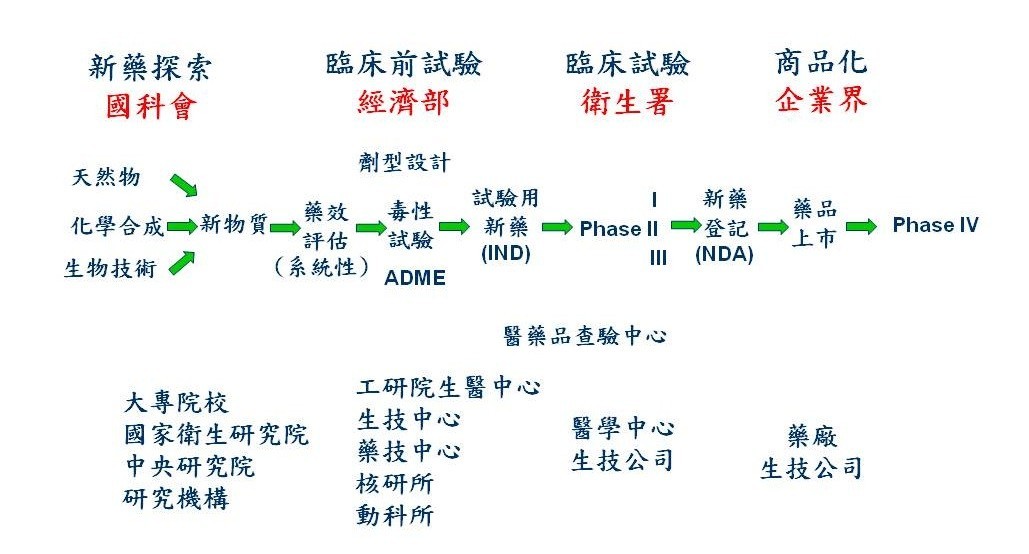

我國政府對生技醫藥之研發投資不小,尤其國科會、經濟部、衛生署都有補助藥物研發計畫之經費。國科會負責藥物探索,包括藥物來源之發掘與藥效之基礎研究,以支援上游之藥物研發;經濟部則補助各法人科專之臨床前研究及產業之藥物研發計畫;衛生署推動臨床試驗與研究中心,並責成醫藥品查驗中心(Center of Drug Evaluation, CDE)協助研發相關之法規問題,以加速藥物研發時程(圖三)。

國科會之補助下,學術界對藥物有關(西藥與中草藥)之研究從未間斷;而且為了促進新藥之研發,國科會及生技醫藥國家型科技計畫並推動產學合作之目標導向研究計畫,對國內新藥研發之學習、人才培訓、與研發體系之建立有所貢獻。近年來國內各大專院校更紛紛成立與藥物研究相關之研究所或中心,以推動上游之藥物研究;為了因應藥物之研發重點目標,許多院校也開始重視有關智慧財產及專利權問題。如此學者專家辛苦研發之成果能夠達成商品化,則不只學者有更多研究經費,校方亦有更充裕之運作基金。

經濟部支援有關生技製藥或特化產業之經費主要來自技術處與工業局。配合產業之研發計畫,經濟部所屬之與生技製藥有關之主要研發機構有:生物技術開發中心(生技中心)、工研院生醫與醫材研究所(工研院生醫所)和製藥工業技術發展中心(藥技中心)三個財團法人;生技中心以發展抗癌小分子與蛋白質藥物為主,工研院生醫所則以抗肝炎、肝癌藥物與醫療器材之研發為重點,而藥技中心著重在植物性新藥及劑型設計技術方面。此外,經濟部亦支援核能研究所(核研所)開發核醫相關之診斷顯影劑與放射性抗腫瘤藥物;動物科技研究所(動科所)則發展基因轉殖動物來生產蛋白質藥物(如凝血第九因子)。

衛生署之食品藥物管理局(TFDA) 專司食品、藥品之管理,衛生署亦支援各醫學中心成立卓越臨床研究中心,並推動轉譯醫學研究、培訓臨床試驗醫事人員等。此外,經費來自衛生署之國家衛生研究院(NHRI)亦設立生物技術與藥物研究所,其目標為建立綜合性之新藥研發設備並延攬人才,以期成為本土新藥研發的先導;因此該所籌設有完整之功能性設施:分子生物、傳統藥物合成、組合化學、自動化高速藥物篩選、分子結構模擬、動物體內藥動力學、及動物疾病模型等實驗室;藥物研發重點以抗癌、抗病毒之新藥為主。

結語

新藥的研發時間很長,所需資金龐大,但是新藥一旦開發成功,其附加價值極高,因此世界各國莫不積極投入。我國之基礎、臨床醫學研究與醫療品質具有已開發國家之水準,但新藥自製之能力卻仍薄弱。近年來在政府及國人之努力下,整體新藥研究體系已漸漸成型,也培育了許多優秀之生物醫學研究人才,漸漸有不錯之研究成果產出。期許未來有更多人才的加入,參與及推動新藥的研發,並協助提昇我國生技製藥之研發能量與競爭力。

原刊載於 科學月刊 第四十四卷第二期