根據生物多樣性之父 Wilson 的親生命假說(biophilia hypothesis)[71],人類一直有著親近動物的本能,且也有研究指出即使在人類幼兒時期就已反應出這種傾向[18, 38, 49],至於為什麼動物對人類構成如此誘人的刺激,目前尚未完全闡明。

與物體相比,生物的確更能吸引人的注意力,據推測這種反應背後的演化學原因,可能源自於關注其他生物之於個體適合度(fitnesss)的重要性[48, 50]。

雖然還未有準確的定義,但獸迷/獸控(furries)被廣泛認為是一群喜歡擬人化[註1]動物(anthropomorphic animals)或擬獸化(zoomorphic)的人類與非生物創作的粉絲,而獸圈(furry fandom / furry community)就是由這些粉絲所組成的社群[23, 58, 61]。許多關於獸文化(furry culture)的學術文章都在討論獸迷族群內的自我認同、社交情況或是獸圈汙名化等議題[23, 29, 45, 60, 61, 62],甚少提及喜歡擬人化動物這類行為的成因。這回,我們將用文獻回顧的方式,帶大家釐清獸迷背後可能會涉及到的演化心理學機制。

一、可愛是什麼?

有沒有想過為什麼比起養小孩,人們越來越偏好於養貓貓狗狗這些寵物?而擬人化動物的卡通形象更是充斥著各類媒體與商品中,他們究竟是擁有怎樣獨特魅力?

1. 可愛就是正義?可愛與生物生存的關係

一個生物之所以會擁有「可愛」的特徵,其目的不外乎是促進其親本或其他生物個體對自己的保護行為及降低被傷害的可能性[1, 15, 24, 51, 66]。在幼年時完全依靠照料者的維持和保護的物種中,這種反應具有明顯的適合度價值,有助於增加後代的生存機會[39],並幫助母親專注於新生兒和依戀調節[67]。

2.可愛吸引人的原因——幼態延續現象

雖然獸迷常被描述成喜歡擬人化動物的族群,但一定程度上,某些現實物種早已經被我們當成是擬人化動物了,例如最常見的寵物物種(即狗和貓等),同時具有形態與行為上的人類嬰兒特徵,因此,可愛某方面也與擬人化脫不了關係。

幼年期的可愛特徵保留至成年期被認為是的馴化副產品[10, 14, 21],而這個過程稱為幼態延續現象(neoteny),它被認為是由於人類對非攻擊性行為的有意識或無意識的選育所造成的[10]。

而據推測,終生幼年特徵(長不大或是嬰兒臉)的存在可能是構成我們對動物特別是寵物的吸引力的基礎[3, 13]。

3.可愛的標準——嬰兒圖式

那有沒有一種標準樣貌,是所有物種都認為可愛的呢?答案是有的!

嬰兒圖式(kindchenschema)由動物行為學家 Lorenz 首次提出[39],是指一組常見於人類和動物嬰兒的面部特徵(如大頭和圓臉、額頭高且突出、大眼睛和小鼻子和嘴巴),在動物行為學中,這種特定的特徵配置被描述為一種能夠觸發用於照顧和對嬰兒情感定向的先天釋放機制,並且在神經生理學上藉由神經成像也證明了其在促進人類養育行為中的作用[25]。

雖然 Lorenz 表示嬰兒圖式反應不僅限於人類[39],但幾乎目前所有的研究及調查都還是在探討人類對於人類或其他動物的嬰兒圖式反應[4, 36, 37, 66],果然可愛的標準似乎還滿主觀的,最終就算是只是對於動物的關注也難以逃離人類中心主義的影響[30]。

4.只要可愛,無論真假都可以

前面討論了關於人們喜歡可愛生物的理論,但這距離解釋獸迷為什麼喜歡獸圖還有一段距離,畢竟前面討論的,多半是指自然狀態下的生物,而非人為加工後的獸圖。為了能更好解釋獸控對獸圖的喜愛,我們可以用超常刺激(supernormal stimuli)的概念,來解釋自然生物與人造物的效果差異。

超常刺激首次由動物行為學家 Tinbergen 所提出[68],是指能夠引發生物產生出比自然狀態下更強烈回饋的一種刺激,而這種刺激多為人為製造,其中提到蠣鷸(Oystercatcher)、鳴禽(Songbird)及灰雁(Greylag goose)等鳥類都有偏好去孵育比起自己更大更醒目的假蛋的現象。參照 Barrett 所提到的[6, 7],超常刺激的型式與載體其實是非常多元的,而其中僅次於「性」的「可愛」,就是最常被各類媒體與商業利用的元素,雖然其文中未提及原因,但可愛確實往往與非人動物連結在一起,而根據許多文獻,人類的確會傾向於偏愛他們認為主觀上具有吸引力或可愛的真實或非真實動物[4, 26, 28, 34, 72]。

5.「人類喜歡擬人化動物」與「人類喜歡動物」要怎麼類比?

Barrett 表示在人類的日常生活中充斥各種超常刺激[7],例如:垃圾食物、電玩、電視、色情創作及網路等,除此以外 Barrett 舉出一款叫做 Cow Clickers 的社群遊戲做例子,裡面就有各式各樣擁有超出常態可愛特徵的卡通乳牛,並且認為這類超常刺激有足夠魅力去吸引人們去遊玩,以及擁有悠久歷史的泰迪熊玩偶,因為相較於真實物種擁有更大的前額及更短的鼻口部等嬰兒特徵,它們才得以流行至今[6]。綜上所述,以獸迷的角度,擁有上述特徵的擬人化動物,一定程度上也可以被視為一種基於觸發親生命假說裡親近動物的本能及嬰兒圖示反應的超常刺激,那麼「人類喜歡擬人化動物」與「人類喜歡動物」是具有行為同源性[註2]behavioral homology)的可能性的確是值得被探討的。

二、 人們對動物的態度

除了可不可愛外,當然還有許多複雜的機制也會影響人類對非人動物的態度,而且耐人尋味的,在某些方面獸圈裡似乎也能看得到人類對其他動物態度的縮影。

1.人類或獸迷喜歡某些物種的前提

根據 Roberts 等人的研究[61],在獸圈這個社群裡,成員與動物的連結也存在多樣的面向,他們認為有三大因素:(1)對一個物種的欣賞或好感(2)與此物種有精神或神秘聯系的感覺,以及(3)與這物種的認同感。事實上人類對動物態度的研究的確是一個極其複雜的問題,它涉及到演化、心理和文化等方面[65]。但是即使不考慮這些,人們對動物的物種傾向也很大程度上取決於動物本身固有的某些屬性,如各種物種的身體和行為特徵很大程度上地影響著人類對動物的感知,並可以解釋道為什麼人們喜歡某些動物或討厭某些動物[65]。

2.影響物種偏好差異的因素

看到這裡必需承認的是,不管是ㄧ般人或是獸迷,現實上對所有動物的態度不可能都一致,如 Kellert 提到有許多因素決定了人類對於其他物種的偏好,如自然價值、人文價值、實用價值、美學價值……等[33]。關於對於某些物種的人類態度和相似性的大量文獻表明,在親緣關係上與人類接近,或在生理、行為或認知上與人類相似的動物往往是首選,且因為牠們會對人們產生更多正向的影響,所以牠們在動物福利和保育方面上往往就會獲得更多的關注[8, 28, 34, 44, 56, 69]。相比之下,人類對親緣關係距離遙遠的動物表現出消極態度(例如:爬蟲類、魚類、無脊椎動物等[11, 32, 57])。類似的現象也反映在獸迷在獸設[註3](fursona)上面的選擇,例如根據Plante等人調查到的樣態可以發現,去除掉非現實物種,相比於親緣關係較遠的爬蟲類及昆蟲等,有更大比例的獸迷都比較偏好選擇哺乳類(尤其是有長遠馴化史的貓科及犬科)做為獸設[53, 54](表1)。

由左至右分別是:混種、狼、狐狸、狗、大型貓、龍、神話生物、貓、其他、囓齒動物、兔子、浣熊、爬蟲類、水獺、鳥類、熊、馬、水生動物、鬣狗、臭鼬、有袋動物、恐龍、鹿、其他貓科、松鼠、雪貂、其他犬科及昆蟲 。圖/ 參考文獻 53

3.其他不同的觀點

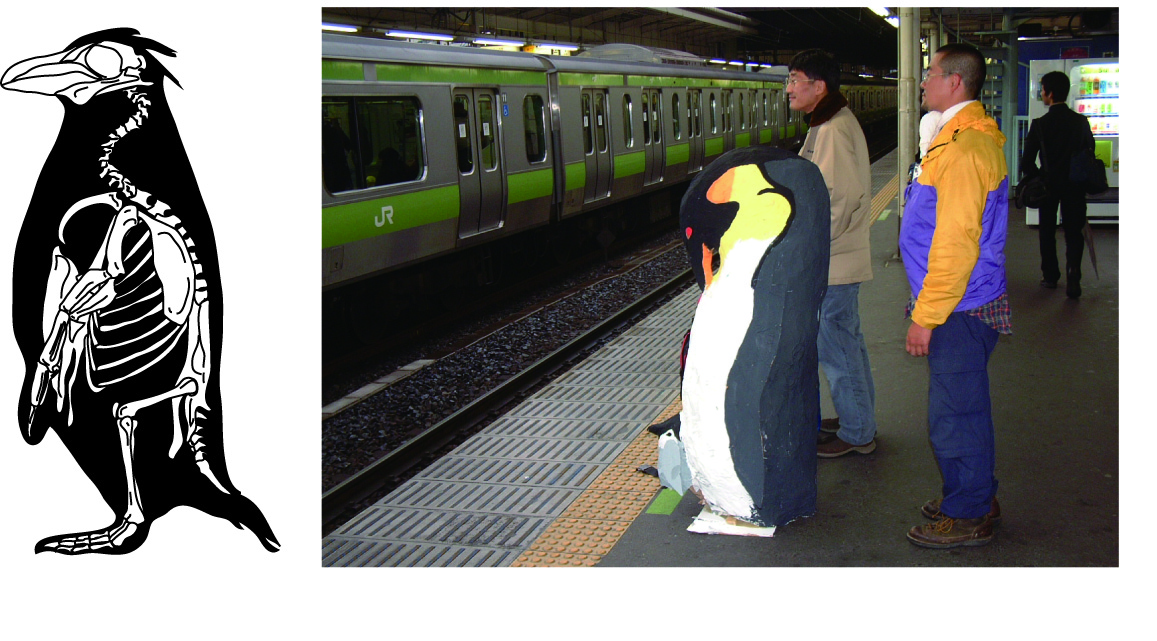

所以照上面所述,照理來講特徵越接近人類的物種或虛擬形象會獲得人類喜愛,但事實上並非如此,例如根據恐怖谷理論(uncanny valley)[47],過於擬人化恐怕產生反效果[46, 64],而其中可能的演化學機制也有很多研究在探討,例如避免病原體[63]、死亡凸顯性[註4](mortality salience)[41]及面部認知失調[40]等。音樂劇— Cats 就是一個經典的例子,劇中的角色造型常常被詬病落於恐怖谷中[52]。

Borgi 和 Cirulli 對幼兒園兒童對多種不同動物種類的偏好進行的分析後,確實符合 “相似性原則”(Similarity Principle)[69],其中顯示出兒童對親緣較近的哺乳類偏好的確顯著大於親緣較遠的無脊椎動物[12](表2)。但在此研究中發現到另一個有趣的例外,與恐怖谷有異曲同工之妙的是,其中與人親緣最近的猴子反而顯示出非常低的偏好水準,此外 Gerbasi 也在文中提到[23],在獸圈也有很少人使用非人靈長類做為獸設的現象。因為事實上人類對於靈長類的負面態度更多會來自於固有的文化、社會及生態等因素的影響[2, 43],這點身為臺灣人的我們也應該感同身受,想想看臺灣獼猴與遊客居民的衝突到底有多嚴重就好。

除此之外,因為型態與行為上與人類相似,在一些文化中猴子常常被象徵著人類的獸性或劣根性[35],Beatson & Halloran 的研究也發現由死亡凸顯性造成的一種相反於相似性原則的現象,尤其是當人類面對於非人靈長類時[9]。就像有些人或有些團體總是宣稱自己喜歡動物、愛護動物,但是還是會下意識地將動物分門別類,這是本能使然不置可否,但關乎到公共利益時還是需要多點理性。

X軸:哺乳類、鳥類、兩棲爬蟲類、無脊椎動物。Y軸:偏好水準。 圖/參考文獻12

三、結語

雖然「人類喜歡擬人化動物」與「人類喜歡動物」這兩種行為的關聯性在學術上尚未有具體的研究,但是人類對於動物的態度本就屬於人 – 動物交互作用,涉及演化學、心理學甚至是動物福利或生物保育學等領域,所以「人類喜歡擬人化動物」也算是種間接的人 – 動物交互作用(human-animal interaction)。雖然在獸迷研究中很少被提到[55],但是學界對於擬人化為動物福利所帶來的利弊一直以來都有討論,且爭議不斷[16, 17, 22],總之無論是擬人化或是超常刺激等,究竟對社會帶來了什麼影響,這裡暫且不會評斷,只希望能理性地討論人類對動物的態度。

總結來說,人類喜歡擬人化動物是一種複雜的行為模式,除了上述提到的各種理論與概念,相信還有更多機制參與其中,但這部分就有待學界研究了。就如同性戀行為或更準確的同性求愛(same-sex courtship),在演化與行為學上的意義已被學界廣泛地研究,並且在諸多物種內都有發現[5, 42, 59],藉由這些科學依據,社會也應該開始常態化地看待同為少數族群的獸迷。

四、註解

- 擬人化是一種將人類心理特徵歸因於其他個體的自然態度[18]。

- 一個分類群或物種內,所觀察到的行為具有功能上的相似性,並且來自於共同的祖先,例如人類所有語言都具有行為同源性[70]。

- 一種代表自己的擬人化動物形象,而且獸設的選擇與個人對於物種的偏好具有顯著的關聯性[61]。

- 以所有人類行為都是出於對自己死亡的恐懼為前提,一種人類的心理防禦機制,用來抑制自己不可避免死亡意識所產生的焦慮[27]。

五、參考資料

1. Alley, T. (1983). Infantile head shape as an elicitor of adult protection. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29(4), 411-427.

2. Anand, S., Binoy, V. V., & Radhakrishna, S. (2018). The monkey is not always a god: Attitudinal differences toward crop-raiding Pet Face: Mechanisms Underlying Human-Animal Relationships. macaques and why it matters for conflict mitigation. Ambio, 47(6), 711-720. doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-1008-5

3. Archer, J. (1997). Why do people love their pets? Evolution and Human Behavior, 18(4), 237-259, doi: 10.1016/S0162-3095(99)80001-4

4. Archer, J., & Monton, S. (2011). Preferences for infant facial features in pet dogs and cats. Ethology, 117(3), 217-226. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2010.01863.x

5. Bailey, N. W., & Zuk, M. (2009). Same-sex sexual behavior and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24(8), 439-446. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.014

6. Barrett, D. (2010). Supernormal stimuli: How primal urges overran their evolutionary purpose. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

7. Barrett, D. (2020). Supernormal Stimuli in the Media. In L. Workman, W. Reader & J. Barkow (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Behavior. (pp. 527-537). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

8.Batt, S. (2009). Human attitudes towards animals in relation to species similarity to humans: a multivariate approach. Bioscience Horizons, 2(2), 180-190. doi: 10.1093/BIOHORIZONS/HZP021

9. Beatson, R. M., & Halloran, M. J. (2007). Humans rule! The effects of creatureliness reminders, mortality salience and self-esteem on attitudes towards animals. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46(3), 619-632. doi: 10.1348/014466606X147753

10. Belyaev, D. K. (1979). Destabilizing selection as a factor in domestication. Journal of Heredity, 70(5), 301-308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109263

11. Bjerke, T., Odegardstuen, T., & Kaltenborn, B. (1998). Attitudes toward animals among Norwegian children and adolescents: species preferences. Anthrozoös 11(4), 227-235. doi: 10.2752/089279398787000544

12. Borgi, M., & Cirulli, F. (2015). Attitudes toward animals among kindergarten children: species preferences. Anthrozoös, 28(1), 45-59. doi: 10.2752/089279315X14129350721939

13. Borgi, M., & Cirulli, F. (2016). Pet Face: Mechanisms Underlying Human-Animal Relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 298. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00298

14. Borgi, M., Cogliati-Dezza, I., Brelsford, V., Meints K, & Cirulli F. (2014). Baby schema in human and animal faces induces cuteness perception and gaze allocation in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00411

15. Brosch, T., Sander, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2007). That baby caught my eye…attention capture by infant faces. Emotion 7(3), 685-689. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.685

16. Brown, C. M., & McLean, J. L. (2015). Anthropomorphizing Dogs: Projecting One’s Own Personality and Consequences for Supporting Animal Rights. Anthrozoös, 28(1), 73-86. doi: 10.2752/089279315×14129350721975

17. Bruni, D., Perconti, P., & Plebe, A. (2018). Anti-anthropomorphism and Its Limits. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2205. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02205

18. Butterfield, M. E., Hill, S. E., & Lord, C. G. (2012). Mangy mutt or furry friend? Anthropomorphism promotes animal welfare. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 957-960. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.010

19. DeLoache, J. S., Pickard, M. B., & LoBue, V. (2011). How very young children think about animals. In P. McCardle, S. McCune, J. A. Griffin, & V. Maholmes (Eds.), How animals affect us: Examining the influences of human–animal interaction on child development and human health. (pp. 85-99). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/12301-004

20. Effie. (2007). Izabela Bujniewicz as Jennyanydots and Wojciech Socha as Skimbleshanks in the musical “Cats” in Roma Musical Theatre in Warsaw, December 2007 r. URL available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Koty_IzaBujniewicz_WojtekSocha.jpg

[accessed 15 June 2021]

21. Frank, H., & Frank, M.G. (1982). On the effects of domestication on canine social development and behavior. Applied Animal Ethology, 8(6), 507-525. doi: 10.1016/0304-3762(82)90215-2

22. Ganea, P. A., Canfield, C. F., Simons-Ghafari, K., & Chou, T. (2014). Do cavies talk? The effect of anthropomorphic picture books on children’s knowledge about animals. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00283

23. Gerbasi, K. C., Paolone, N., Higner, J., Scaletta, L. L., Bernstein, P. L., Conway, S., & Privitera, A. (2008). Furries from A to Z (anthropomorphism to zoomorphism). Society & Animals: Journal of Human-Animal Studies, 16(3), 197-222. doi: 10.1163/156853008X323376

24. Glocker, M. L., Langleben, D. D., Ruparel, K., Loughead, J. W., Gur, R. C., and Sachser, N. (2009a). Baby schema in infant faces induces cuteness perception and motivation for caretaking in adults. Ethology, 115(3), 257-263. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01603.x

25. Glocker, M. L., Langleben, D. D., Ruparel, K., Loughead, J. W., Valdez, J. N., Griffin, M. D., … Gur, R. C. (2009b). Baby schema modulates the brain reward system in nulliparous women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(22), 9115-9119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811620106

26. Gould, S. J. (1979). Mickey mouse meets Konrad Lorenz. Natural History Magazine, 88(5), 30-36.

27. Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of the need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189-212). New York, NY, USA.

28. Gunnthorsdottir, A. (2001). Physical attractiveness of an animal species as a decision factor for its preservation. Anthrozoös, 14(4), 204-215. doi: 10.2752/089279301786999355

29. Hsu, K. J., Bailey, J. M. (2019). The “Furry” Phenomenon: Characterizing Sexual Orientation, Sexual Motivation, and Erotic Target Identity Inversions in Male Furries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(5), 1349-1369. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1303-7

30. Jenkins, L. (2015). The Touch of Nature Has Made the Whole World Kin: Interspecies Kin Selection in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. doi: 10.1016/s0378-777x(78)80028-6

31. Julia, W. (2014). Anthrocon 2014. URL available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/foxgrrl/14843099909 [accessed 17 June 2021]

32. Kellert, S. R. (1993). Values and perceptions of invertebrates. Conservation Biology, 7(4), 845-855. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.740845.x

33. Kellert, S. R. (1997). The Value of Life: Biological Diversity and Human Society. Washington: Island Press.

34. Knight, A. (2008). “Bats, snakes and spiders, Oh my!” How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 94-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.001

35. Knight, J. (1999). Monkeys of the move: the natural symbolism of people-macaque conflict in Japan. The Journal of Asian Studies, 58(3), 622-647. doi: 10.2307/2659114

36. Lehmann, V., Huis in‘t Veld, E. M. J., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2013). The human and animal baby schema effect: Correlates of individual differences. Behavioural Processes, 94, 99-108. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.01.001

37. Little, A. C. (2012). Manipulation of infant-like traits affects perceived cuteness of infant, adult and cat faces. Ethology 118(8), 775-782. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2012.02068.x

38. Lobue, V., Bloom Pickard, M., Sherman, K., Axford, C., and DeLoache, J. S. (2013). Young children’s interest in live animals. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 57-69. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2012.02078.x

39. Lorenz, K. (1943). Die angeborenen Formen möglicher Erfahrung. Zeitschrift Für Tierpsychologie, 5(2), 233-519. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1943.tb00655.x

40. MacDorman, K. F. (2005). Mortality salience and the uncanny valley. 5th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, 2005., 399-405. doi: 10.1109/ICHR.2005.1573600

41. MacDorman, K., Green, R., Ho, C., Koch, C. (2009). Too real for comfort? Uncanny

responses to computer-generated faces. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(3),

695-710. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.026

42. Mann, J. (2006). Establishing trust: socio-sexual behaviour and the development of male-male bonds among Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins. In V. Sommer & P. L. Vasey (Eds.), Homosexual Behaviour in Animals (pp. 107-130). Cambridge University Press.

43. Margulies, J. D., & Karanth, K. K. (2018). The production of human-wildlife conflict: A political animal geography of encounter. Geoforum, 95, 153-164. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.011

44. Martín-López, B., Montes, C., and Benayes, J. (2007). The non-economic motives behind the willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 139(1-2), 67-82. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.06.005

45. Mock, S.E., Plante, C., Reysen, S., & Gerbasi, K. (2013). Deeper leisure involvement as a coping resource in a stigmatized leisure context. Leisure/Loisir 37(2), 111-126. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2013.801152

46. Moosa, M. M., & Ud-Dean, S. M. M. (2010). Danger Avoidance: An Evolutionary Explanation of Uncanny Valley. Biological Theory, 5(1), 12-14. doi: 10.1162/biot_a_00016

47. Mori, M. (1970). The uncanny valley. Energy, 7(4), 33-35.

48. Mormann, F., Dubois, J., Kornblith, S., Milosavljevic, M., Cerf, M., Ison, M., et al. (2011). A category-specific response to animals in the right human amygdala. Nature neuroscience, 14(10), 1247-1249. doi: 10.1038/nn.2899

49. Muszkat, M., de Mello, C. B., Muñoz, P., Lucci, T. K., David, V. F., Siqueira, J., & Otta, E. (2015). Face scanning in autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: human versus dog face scanning. Frontiers in psychiatry, 6, 150. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00150

50. New, J., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2007). Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(42), 16598-16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703913104

51. Nittono, H., Fukushima, M., Yano, A., & Moriya, H. (2012). The Power of Kawaii: Viewing Cute Images Promotes a Careful Behavior and Narrows Attentional Focus. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e46362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046362

52. Nolan, M. (2019). The problem with Cats, The Lion King & the uncanny valley. URL available at: https://www.rte.ie/culture/2019/0730/1065967-the-problem-with-cats-the-lion-king-the-uncanny-valley/

[accessed 20 May 2021]

53. Plante, C. N., Mock, S., Reysen, S., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2011). International Anthropomorphic Research Project: Winter 2011 Online Survey Summary. URL available at: https://sites.google.com/site/anthropomorphicresearch/past-results/international-online-furry-survey-2011 [accessed 20 May 2021]

54. Plante, C. N., Reysen, S., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2016). FurScience! A summary of five years of research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Waterloo, Ontario: FurScience. URL available at: https://sites.google.com/site/anthropomorphicresearch/past-results/international-online-furry-survey-2011 [accessed 20 May 2021]

55. Plante, C. N., Reysen, S., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2018). “Animals Like Us”: Identifying with Nonhuman Animals and Support for Nonhuman Animal Rights. Anthrozoös, 31(2), 165-177. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2018.1434045

56. Plous, S. (1993). Psychological mechanisms in the human use of animals. Journal of Social Issues, 49(1), 11-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00907.x

57. Prokop, P., Tolarovićová, A., Camerik, A., & Peterková, V. (2010). High school students’ attitudes towards spiders: a cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Science Education, 32(12), 1665-1688. doi: 10.1080/09500690903253908

58. Půtová, B. (2013). Prehistoric sorcerers and postmodern furries: Anthropological point of view. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 5(7), 243-248. doi: 10.5897/IJSA12.052

59. Rahman, Q., & Hull, M. S. (2005). An empirical test of the kin selection hypothesis for male homosexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34(4), 461-467. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-4345-6

60. Reysen, S., Plante, C. N., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2015). Ingroup bias and ingroup projection in the furry fandom. International Journal of Psychological Studies 7(4): 49-58. doi: 10.5539/ijps.v7n4p49

61. Roberts, S. E., Plante, C. N., Gerbasi, K. C., & Reysen, S. (2015a). The Anthropomorphic Identity: Furry Fandom Members’ Connections to Nonhuman Animals. Anthrozoos A Multidisciplinary Journal of The Interactions of People & Animals, 28(4), 533-548. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.1069993

62. Roberts, S. E., Plante, C. N., Gerbasi, K. C., & Reysen, S. (2015b). Clinical interaction with anthropomorphic phenomenon: Notes for health professionals about interacting with clients who possess this unusual identity. Health and Social Work, 40(2), e42-e50. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlv020

63. Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. E. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review, 94(1), 23-41.

64. Schwind, V., Leicht, K., Jäger, S., Wolf, K., & Henze, N. (2018). Is there an uncanny valley of virtual animals? A quantitative and qualitative investigation. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 111, 49-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2017.11.003

65. Serpell, J. A. (2004). Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Animal Welfare, 13, 145-151.

66. Sherman, G. D., Haidt, J., & Coan, J. A. (2009). Viewing cute images increases behavioral carefulness. Emotion, 9(2), 282-286. doi: 10.1037/a0014904

67. Sprengelmeyer, R., Perrett, D. I., Fagan, E. C., Cornwell, R. E., Lobmaier, J. S., Sprengelmeyer, A., … Young, A. W. (2009). The Cutest Little Baby Face. Psychological Science, 20(2), 149-154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02272.x.

68. Tinbergen, N. (1953). The Herring Gull’s World. London: Collins.

69. Tisdell, C., Wilson, C., & Swarna Nantha, H. (2006). Public choice of species for the ‘Ark’: phylogenetic similarity and preferred wildlife species for survival. Journal for Nature Conservation, 14(3-4), 266-267. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2006.07.001

70. Wenzel, J. W. (1992). Behavioral Homology and Phylogeny. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 23(1), 361-381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.23.110192.002045

71. Wilson, E. (1984). Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

72. Woods, B. (2000). Beauty and the beast: preferences for animals in Australia. Journal of Tourism Studies, 11(2), 25-35. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.200110918